In the past three weeks, an unprecedented surge in COVID-19 cases has engulfed Florida. On June 1, the state’s seven-day running average for new cases—used to smooth the jitters in daily totals due to weekend testing drops and reporting backlogs—stood at 726. By June 15, the seven-day average had more than doubled to 1,775 daily cases, exceeding the state’s early peak in April. By the end of June, the seven-day average had almost quadrupled to 6,990 daily cases. Less than a week into July, the seven-day average for daily new cases now stands at more than 9,200, despite decreased testing and reporting over the Independence Day weekend.

With a population of 21 million, Florida now has more new cases per day than any other US state, including two other larger states with major outbreaks, Texas (population 29 million) and California (population 40 million).

Back in April, things looked very different. By April 15, Florida had confirmed just over 22,500 cases of COVID-19, while in the pandemic’s early epicenter, New York had confirmed almost 215,000 cases.

In a televised interview, Dr. Deborah Birx, coordinator of the White House’s coronavirus response, singled out Florida’s COVID-19 public health dashboard as exemplary because it offered case and testing data at the county and zip-code level. Florida also stood out as one of the first US states to break out cases and deaths by race and ethnicity. And although it took threats of lawsuits to get the Florida Department of Health to release weekly reports on COVID-19 in long-term care facilities and correctional facilities, the data was eventually published. But other crucial data remains out of public reach, and the way Florida releases much of its data has also made data compilation a challenge for researchers—both for reasons unique to Florida’s data, and because of problems common to many other states.

Our aim at The COVID Tracking Project is to compile the data states and territories provide in the most useful and transparent way we can. In this post, we’ll walk through the things we’ve learned about Florida’s COVID-19 data, the challenges we’ve encountered in compiling it, and some problems that we’ve been unable to solve.

Missing COVID-19 hospitalization data

Update: As of July 10, ten days after the governor’s office told the Miami Herald that current hospitalization data would be incorporated into the state’s COVID-19 reporting within a few days, the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration began publishing data by county for “Hospitalizations with Primary Diagnosis of COVID.” To our knowledge, this data has not appeared on the Florida Department of Health’s COVID-19 website. We are seeking clarification about which patient populations this data includes.

States report new COVID-19 cases and test totals days or even weeks after the tests are performed. This lag between testing and reporting can stretch longer and longer as outbreaks worsen. Death data, which epidemiologists sometimes characterize as a better measure of an outbreak’s severity, lags even more than testing data. This makes hospitalization numbers one of the best ways to understand the true size and severity of COVID-19 outbreaks in something closer to real time, particularly in areas where testing capacity has been overwhelmed.

Only three US states—Florida, Hawaii, and Kansas—fail to publish data on how many of the state’s COVID-19 patients are currently hospitalized. Of those three states, Florida has the largest COVID-19 outbreak by far.

Instead, the state releases only cumulative hospitalizations and ER admissions for COVID-19 patients. As discussed in our recent post on hospitalization data, it’s not possible to calculate current hospitalizations from cumulative totals. Since April, the Agency for Healthcare Administration has released data on hospital-bed and ICU capacity and utilization independently of the Florida Department of Health. This data is useful for understanding which hospitals may be running out of capacity, but it is not COVID-19 specific.

But the hospitalization data gap for Florida may be about to close. Miami Herald journalist Ben Conarck reported on June 30 that the governor’s office told him that “current hospitalizations will be incorporated into the state’s COVID reporting in the next few days.” When we queried the Florida Department of Health, they told us via email that they don’t track hospitalization data in their system—and that current hospitalization data won’t be included in the detailed state- and county-level PDF reports they produce each day. However, a spokesperson for the Florida Department of Health told Bloomberg in late June that the data will be published “alongside other publicly available data on cases.” As of this morning, eight days after the initial announcement, the data has not yet been published.

Missing data on probable cases and deaths

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, working closely with the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, advises all US states and territories to report “probable” COVID-19 cases and deaths. (We broke down the strict requirements for a case to be considered probable here on the blog earlier this month.)

When testing capacity is overwhelmed and it becomes harder to get lab confirmation for suspected cases of COVID-19, lab tests can no longer capture the full impact of an outbreak. In these circumstances, data on probable cases and deaths becomes crucial to understanding the full extent of the outbreak. Florida does not report probable cases or deaths.

Mixed PCR and antigen testing data

The FDA has approved two different COVID-19 diagnostic tests: PCR tests and antigen tests. The PCR test is a molecular test that detects the presence of the genetic material of the virus. It is seen as the gold standard of diagnostic tests. It is the most accurate test available, but it can take days to get test results. Antigen tests are a newly approved, rapid form of COVID-19 diagnostic test that detects the presence of a specific protein on the surface of the virus. Results are quick, but they are not as sensitive as PCR tests and have a higher chance of false negatives.

On July 1, the Florida Department of Health started mixing antigen test results with PCR test results and calculating an overall percent-positive rate using this commingled data. The state does not break out the number of each type of test reported. Because these tests perform differently and antigen tests are more likely to provide false negative results, these tests should not be combined in reports. They should also not be used to calculate the percent positivity, which is likely to be artificially lowered by the inclusion of a test with a greater percentage of false negatives.

Antigen tests are also not considered to be “confirmatory” tests, so people with positive antigen tests alone don’t count as confirmed cases of COVID-19. In fact, they don’t even count as probable cases without additional epidemiological or clinical evidence. Antigen test totals and results should be provided separately.

Incomplete data on COVID-19 in long-term care facilities

Long-term care facilities have especially been hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. The New York Times reports that 11% of all US county’s cases have occurred in these facilities and that they account for 43% of all US COVID-19 deaths. Florida’s facilities have already seen large COVID-19 outbreaks, and the 1,994 deaths in long-term care facilities to date account for 50% of the state’s total COVID-19 deaths.

Until mid-April, Florida did not publish any data about COVID-19 in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. After local news organizations threatened public-records lawsuits, Florida began publishing some data on COVID-19 in nursing homes and assisted living facilities in April. But major deficiencies remain:

The state also does not report cumulative long-term care facility cases, instead reporting “the information available for current residents and staff with cases as of yesterday’s date.” A resident or staff member of a long-term care facility who has recovered from the virus will not be listed on either report. A resident or staff member who was infected with COVID-19 and has a COVID-19 related death will not be included as a positive case in future reports and will be listed in the death report only.

Florida reports cumulative deaths once a week, separately from its state and county COVID-19 reports, in a non-machine-readable PDF with no total listed for deaths, which must be extracted and summed to find out how many nursing home residents have died.

Florida does not publish the counts of how many residents at each facility have been tested in its long-term care facility report.

Eight out of every ten people who have died of COVID-19 in the United States have been age 65 or older. According to the Population Reference Bureau, Florida’s population of 21 million people includes more than 4.4 million residents over the age of 65. Of this large vulnerable population, some of the very most vulnerable live in nursing homes or assisted living facilities. We would like to see the state immediately begin providing much more thorough reporting on COVID-19 in long-term care facilities.

Incomplete reporting on COVID-19 in prisons and jails

Florida’s reporting from correctional and detention facilities has also been patchy. The Florida Department of Health discloses the total number of correctional facility cases in the daily report by county, but not in the report by state. A report produced by the Florida Department of Corrections includes substantially richer data, including figures for total tests performed on inmates, inmates in medical isolation, and cases among prison staff.

The Florida Department of Emergency Management confirmed to our reporter that Florida's correctional facilities reporting covers exclusively state prisons, which means that COVID-19 cases and deaths in Florida's 67 county jails and many detention centers are not distinguished from other cases and deaths in the state's data.

COVID-19 is especially hard to control in a crowded and mostly-closed environment. The Florida Department of Health should report COVID-19 cases and deaths reported at any prison, jail, or detention facility in the state. It also should report all testing results at these facilities. Additionally, the data the state does release on correctional facilities doesn't include demographic data to go along with it. Given the well established links between race and disparate rates of prosecution and incarceration and the disproportionate effects COVID-19 is having on people of color, race and ethnicity data should be released along with COVID-19 counts.

Incomplete race and ethnicity data

Per the OMB’s 1997 Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, there are five minimum categories for data on race: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Florida only releases data on four race categories: White, Black, Other, and Unknown.

Additionally, although age, sex, race, and ethnicity data are all collected and contained in the Florida Department of Health’s systems at a high level of granularity, only age and sex are incorporated into the cases and deaths case line data. That means researchers studying race and ethnicity issues of COVID-19 must run special code to scrape the material in Florida’s other data sources. It’s essential for this data to be made available in a more straightforward manner so it can be compiled and analyzed.

Due to COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on communities of color, it is essential for researchers, non-profit organizations, and other non-governmental organizations to have the ability to compile, analyze, and address policy concerns to reduce these impacts.

Opaque percent-positive calculations

Florida reports testing data in ways that make it difficult to calculate percent positivity—a metric that the CDC uses to refer to the percentage of COVID-19 tests that come back positive, out of all tests performed. Florida does their own quite specific calculations for percent-positive, some of which can’t be replicated by the public, because the state doesn’t report the numbers it uses to derive them.

On the public dashboard, Florida provides a weekly look at percent-positive rates, which offers a weekly average percent-positive data point for past weeks. This data, provided as a line graph, does not include a calculation method.

In the daily PDF report from the Florida Department of Health, the state offers two percent-positive bar charts, and notes that the percentages in these charts are derived by dividing “the number of people who test positive for the first time” by “all the people tested that day, excluding people who have previously tested positive.” The Florida Department of Health does not release daily data for the number of people who tested positive for the first time (or for repeat positives) so there is no way for the public to independently verify the Department of Health’s published percent-positive rate.

The Florida Department of Health’s data dictionary includes the calculation for a weekly percent-positive rate, but not a daily percent-positive rate.

Inconsistent or missing data on non-residents

Florida attracted 131 million visitors in 2019, according to Visit Florida, the state’s official tourism marketing corporation. Visit Florida’s research team uses hotel bookings to calculate the effects of COVID-19 on the tourism industry to date, and found that while bookings dropped to less than 25 percent of 2019’s volume for the equivalent week in late April 2020, by June 14, they were back to almost 50 percent.

Large numbers of out-of-state visitors are once again traveling to Florida’s cities and beaches, and in a state with a substantial tourism industry, failing to clearly and consistently report cases, hospitalizations, and deaths of non-resident COVID-19 patients who fell ill while in Florida creates a potentially major gap in public health information.

Florida’s reporting dashboard includes some data on non-residents with COVID-19, but incompletely and in ways that reduce their visibility:

In the main tab of the dashboard, “total cases” includes non-residents with lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19.

“Hospitalizations” reports data for Florida residents only, but without a clear label.

As of June 30, non-resident deaths are included on the dashboard, but the deaths totals are not summed.

The “Florida Testing” section of the dashboard mixes residents and non-residents, while the “Cases by County” and “Cases by Zip Code” sections do not.

The “Health Metrics” section, which lists emergency department visits from people with influenza-like and COVID-like illnesses as well as laboratory testing positivity, excludes non-residents.

The top-level web page for Florida’s COVID-19 data also provides resident and non-resident data in ways that are difficult to interpret and are inconsistent with the dashboard.

These inconsistencies make it difficult to compile the data accurately, and have also led to confusion and incorrect numbers in media reports. To date, 102 non-Florida residents have officially died from COVID-19 in Florida, nearly 3% of the total death count, while 3,291 non-Florida residents are included in positive cases (1.5%).1

Re-opening metrics not updated

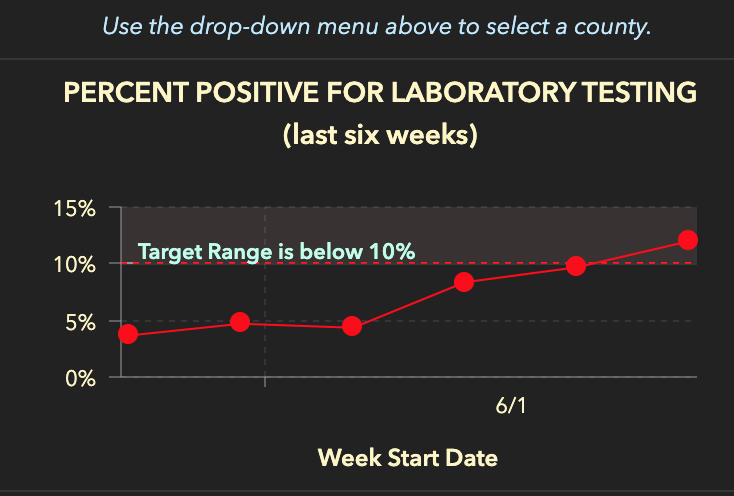

Florida’s COVID-19 Data and Surveillance Dashboard monitors multiple heath metrics to evaluate the state’s progress in fighting the pandemic. These health metrics are: emergency department visits with influenza-like illness, documented new cases, emergency department visits with COVID-like illness, and percent positivity for laboratory testing.

The Re-Open Florida Task Force identified these metrics as important “to evaluate each county’s readiness to begin a phased return to pre-pandemic activity.” These metrics are weekly measures; updates on the dashboard (and in the county reports) lag by a week. The statewide graphs for influenza-like illness and emergency department visits with COVID-like illness are included in the county report, but not the statewide report.

The Task Force report published on April 29 states that the Florida Department of Health criteria is a downward trajectory in ER visits for influenza-like and COVID-like illnesses, as well as a decrease in documented new cases or percent-positive rates. No timeframes for these metrics were published in the Florida report, but the White House report on which it was based establishes a two-week downward trend as the correct metric.

As of July 8, none of Florida’s 67 counties satisfy the state’s reopening criteria on a two-week timeline, according to an analysis of Florida's case line data by The COVID Tracking Project and confirmed by data compiled by former Florida Department of Health data scientist Rebekah Jones. If Florida used a less restrictive timeline than the White House and looked a the numbers over a single week, only three counties would meet the requirements. Nevertheless, Florida Gov. DeSantis announced in a press conference that Florida will not reverse its reopening.

Data reliability

Although Florida did provide more accessible data on COVID-19 earlier on than most other states of its size and population (21 million as of a 2019 census estimate), the data provided by the Florida Department of Health has been plagued by reliability issues. The department uses a GIS data hosting service called ArcGIS provided by Esri and used by many other state agencies, but Florida’s service has been unusually unstable and is regularly unavailable while updates are being made. This occasionally leads to prolonged outages, which often ripple out to the Florida Department of Health’s own dynamic ArcGIS dashboard. The Florida Department of Health doesn’t notify or report on such downtimes ahead of time or afterwards, which has led researchers and journalists to rely instead on painstakingly parsing non-machine-readable data provided by the Florida Department of Health in snapshot PDF reports published daily and weekly on its COVID-19 homepage.

Florida’s data can be much better

Florida is far from a COVID-19 data desert. The state publishes a total of eight different COVID-19 reports with various update cadences. But the state is still missing critically important information, stashing data on COVID-19 in some of the state’s most vulnerable communities in obscure PDFs, and presenting many data points in inconsistent and confusing ways.

For the past four months, as we have compiled the 56 sets of state and territory numbers that make up our national COVID-19 dataset, Florida’s dataset (or indeed many datasets) has remained one of the most difficult to work with and interpret, despite the efforts of local journalists and guidance from staff at the Florida Department of Health. Our state grades system, developed to recognize states that report various top-line COVID-19 data points in any form, currently awards Florida an A grade. Future iterations of the grading system will include more stringent requirements connected with many of the recommendations we offer below.

Six ways to improve Florida data right away

As Florida’s outbreak continues to surge, endangering Florida’s most vulnerable residents and overwhelming testing capacity, we offer the following recommendations for immediate changes that would substantially improve visibility into the pandemic’s severity and effects.

Release the following data points, at the state and county level and for residents and non-residents: daily and cumulative data on probable cases and deaths, current COVID-19 patients admitted to a hospital, in the ICU, and on ventilators.

Release all case, hospitalization usage, and death data by race and ethnicity, consistent with OMB’s minimum categories noted above.

Report cases and deaths at nursing homes, assisted living facilities, prisons, jails, and detention centers within two days of receiving confirmation of COVID-19 diagnostic tests or being notified of COVID-19 deaths.

Report PCR and antigen tests separately to avoid mixing results from tests with different rates of false negatives.

Publicly release the raw daily counts used to make the Florida Department of Health’s percent-positive calculation, specifically the (currently unavailable) number of first time positive tests each day compared to retests.

Release all of this data and all other COVID-19 reports at the state and county level as machine readable documents.

The COVID Tracking Project is part of a consortium of COVID-19 data organizations working on a detailed set of data standards for future publication. If you’re interested in helping us push for better COVID-19 data, sign up for our low-volume email list.

Acknowledgements

Artis Curiskis, Sarah Hoffman, Erin Kissane, Jessica Malaty Rivera, Amber Wojcek, and many other members of The COVID Tracking Project contributed to this piece. Florida geographic data scientist Rebekah Jones worked with many COVID-19 researchers to help locate data sources for missing Florida data. Several current staff members at the Florida Department of Health have responded to many of our requests for information, in some cases as authorized representatives of the department, and in others as scientists trying to support researchers working on COVID-19 data. We have omitted their names from our reporting to protect them from potential reprisals.

1 Data downloaded from the Florida Department of Health’s open data site on July 8 may also suggest that there are disparities in resident and non-resident treatment and patient outcomes. 13.98% of non-residents with confirmed COVID-19 visited the emergency department, versus 12.58% of residents. 9.42% of non-residents with confirmed COVID-19 were admitted to the hospital, versus 7.60% of residents. 3.10% of non-residents with confirmed COVID-19 died, versus 1.76% of residents. One explanation for this disparity may be that more non-residents are being tested if they become severely ill.

Rebecca Glassman has a Master’s in Public Health and is a public health researcher in academia. Opinions expressed are her own.

Olivier Lacan is a software engineer and adoptive Floridian analyzing the sunshine state as a COVID Tracking Project volunteer since March 2020.

Latest posts

20,000 Hours of Data Entry: Why We Didn’t Automate Our Data Collection

Looking back on a year of collecting COVID-19 data, here’s a summary of the tools we automated to make our data entry smoother and why we ultimately relied on manual data collection.

A Wrap-Up: The Five Major Metrics of COVID-19 Data

As The COVID Tracking Project comes to a close, here’s a summary of how states reported data on the five major COVID-19 metrics we tracked—tests, cases, deaths, hospitalizations, and recoveries—and how reporting complexities shaped the data.

How Probable Cases Changed Through the COVID-19 Pandemic

When analyzing COVID-19 data, confirmed case counts are obvious to study. But don’t overlook probable cases—and the varying, evolving ways that states have defined them.